In conversation with Barbie - Living Arts Cranberra

“Memoir is an interesting form of writing, as one always speculates what has been left unsaid. In A Particular Woman, we fancy this is also true but Ashley Dawson-Damer has generously shared a great deal. She speaks with honesty and heart about many aspects and periods of her life and times (she was born in 1945, as she once proudly announced in a Board meeting, when her capacity and experience were subtly called into doubt). In exploring the most challenging times of her life, the author allows us a very clear insight into what drives her, whether that be in family matters or in her professional life.” - Barbie Robinson (For the full story and to listen to this interview, please visit Barbie’s website here)

Barbie:

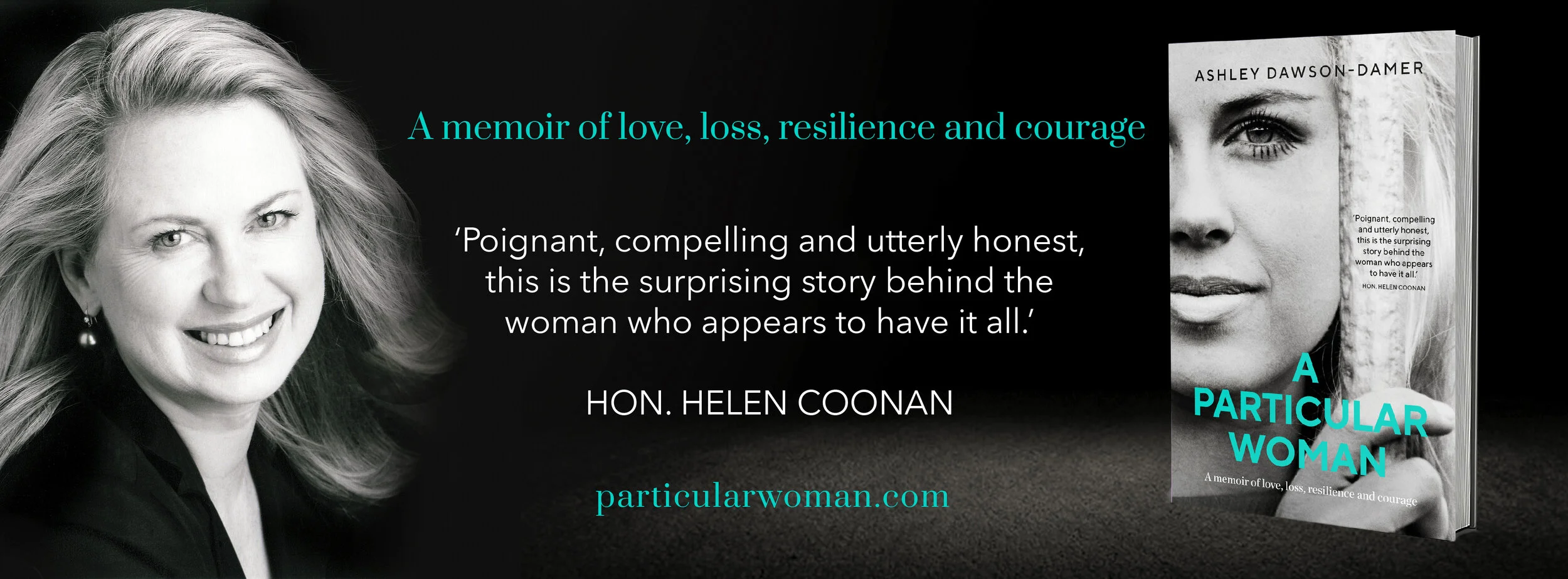

It’s a pleasure for me to be speaking to Ashley Dawson-Damer, whose book, A Particular Woman, has just been published by Ventura Press. It is a memoir.

Welcome to Living Arts Canberra, Ashley.

Ashley Dawson-Damer:

Thank you, Barbie. It’s very good to be here.

Barbie:

Ashley, the first thing that always leaps into my mind when I read a memoir, is to wonder why that person has decided to set their life down, bare their life, before the general public. Because many people that I know, and I’m probably included in that category, were we to write a memoir, we would have to leave out such vast chunks about our life. You seem to not have had qualms about that. Tell me about the memoir.

Ashley:

Well, Barbie, I had two go's before this one. My first two books were health books for women with an element of my life in it. I self-published them because I wanted to handle the whole thing.

The first one was quite popular – I sold over a thousand copies. Both mentioned the suburbs because that’s where I lived most of the time. And the responses to me were, “Ashley, we love your second health book. We love your first health book. You’ve given us a bit of your life in each. Can you ditch the health and give us your life?”

I realized that there was an interest in this funny life I’ve had – ups and downs, and happiness and sadness. So I thought, “Well, go ahead and write about it.” I got tremendous responses from people who thought they knew me but there have been so many facets of my life not everyone has known except a few. I’ve been brave enough in writing about my life, I suppose, but I’ve enjoyed doing it.

Barbie:

Yes, and I suppose it’s true about everyone that we are a bit of a mystery to people. People know bits of us but they never know all about us.

As many people may not have done in speaking to you about the book, I'd like to start with the current part of the book, which is the end. You’ve written chronologically, and it’s a bit of a selfish reason on my part because I’m particularly interested in the issue of women on boards. And much of that last section focuses on the work you’ve done on major Arts boards in Australia, The National Gallery, NIDA, Australian Opera and so on – all really are major Arts boards. I’m really interested to know your take on being a woman on a board and why has it been important to you to make a contribution in that way?

Ashley:

Well, we women start off in funny places. We often don’t know where our lives are going. There are actual events in our lives that interrupt our career paths.

As for me, I’ve always liked raising money. In my children’s school, I was very involved in that. And one of the things you find out on a school committee is that you better come across with what you’ve promised or the mothers will go down on you like a ton of bricks. I learned that discipline well.

When I started moving deeper into the Arts world – and that began with Museum of Sydney – I was appointed to the Foundation board. I was successful with fundraising. Then I was appointed to the NIDA board, which was where I think my talent just flourished because I’ve always been a political animal – I liked talking to my politicians. I have a certain point of view but I will always give loyalty to whoever leads our country. I found that I had no trouble talking to politicians and in those days, Canberra was wide open. I managed to achieve 25 million dollars’ worth of funding for the NIDA new theatre. It was a bit of a sad story because I was naive enough to believe that although I may not be honored for it, it might be remembered that I had raised the money. But it was quickly forgotten. It was one thing to scramble after the money, and some people just planted their glory.

So I departed that board after my 16 years of two terms. I didn’t renew my term. My politician friends gained an inkling of this and decided that the prime minister, John Harold, appointed me to the National Gallery Board, which was the jewel in the crown. Truly, I was quite overwhelmed by the honor of it and thought, “Am I good enough?” I walked into a room of powerful, very powerful men, most of them are tall, and I thought, “Ashley, you can do it. You’re a bit scared but you can do it.” I settled into that and I was there for nine years.

One of the things I loved about staying on a board was that you could make changes for people who mattered, for those who worked in the organization, for people who were vulnerable, for people who didn’t have a voice. I would use my voice to improve the working conditions for people, to spread the word that we must bring the whole of Australia into the story of this wonderful Arts world.

Barbie:

Yes, and isn’t it a shame that it’s such a struggle to get the Arts to prominence in Australia? It’s noticeable now with the COVID-19 restrictions. There’s such an emphasis in getting football back and I mean I know I shouldn't say this aloud, but I’m much more interested in getting the National Gallery open or the National Museum. It’s just a struggle all the time in the Arts.

I want to pick up on what you've said earlier, “Well, Ashley, you’re a bit scared, but you can do it.” That, to me, has echoed through the book right from the very beginning.

You had a series of family-related dramas to face and overcome. Each time you have felt a little daunted but you’ve gone ahead. That included a rather accidental entry into the modeling world. Tell us, if you would, Ashley, about that personal story of modeling and why that was such a very convenient and excellent way for you to earn a living at that time in your life.

Ashley:

Well, we can be dogged by, people call it good luck – I find it part of the Universe. What does the Universe have out there for you? And you really have to take your life in your hand and say, “I can achieve this. I can overcome this.”

I had my second baby. Both of my children are adopted after moving. As you realized, I have four babies. My second baby came along. This has nothing to say about my first husband. He was a good man in his way, but the marriage had started to fail and the little girl came along in replacement for my baby who died. She was six weeks old then. At seven months, the marriage disintegrated. The adoptions department came to take her back and that was another battle I fought quietly – they don’t do publicity when you’re talking about adoption. They allowed her to live with me but I couldn't leave her, and my husband was not supporting her. He wasn’t allowed to have anything to do with her. Somehow, I had to make money but I couldn’t leave the little thing. So I searched for something where I could take my baby with me every day.

Lucky enough, I was asked if I’d like to do some modeling. The baby would be on my hip and I would roll up and they would say, “We didn’t know you were going to bring your baby.” And I’d say, “Well, this baby is a different baby. She won’t get in the way.” She learned how to deal with the cables, and people used to spoil her. She would sit in the chair and watch her mother going through the routine, the retakes. I don’t think she actually thought we were two people. I think she thought she was me, because at one casting she just slid off my lap. She was 18 months old. She took my composite cards and handed them around the room. I’m still not sure if she's thought around this young so much so that she does know we’re two people, because we were a team and I was very lucky. I did this for two years and the man I was to marry, I think, partly fell in love with me because he saw me every night on television, in commercials.

I haven’t had a fortunate life.

Barbie:

Indeed, it has not been a fortunate life, without lots of hard work to make that fortune happen though. We often see people who are regarded as being lucky, but there’s been a lot of sweat going into the luck.

Ashley, you’ve spoken there about your daughter Adelicia and the bond, closeness and indeed her maturity. And that came to the fore, very much after the terribly tragic death of John. She was just a very young thing and yet she seemed to step into the role of supporting you to the hilt and taking on many adult tasks.

Your marriage to John was a very happy and felicitous one and living at Oran Park was another big project for you because the house, Oran Park homestead, the heritage-listed homestead, was in a state of disrepair, wasn't it? You had to go to all sorts of lengths to make it much more habitable. Tell us a little bit about the Oran Park story, please.

Ashley:

When I saw Oran Park for the first time, the man who was to be my husband used to describe it as his farmhouse. So when I first visited it, I thought, “My goodness! That’s not a farmhouse – that's Gone with the Wind!”

And then we named Ashley after Leslie Howard in Gone with the Wind. Gone with the Wind has dogged me all my life. Here, I had Tara in front of me. And when we married, I thought, “Have I the strength?” I’ve been modeling and working so hard – I was exhausted. And I had these two darling children. But I found them a fabulous father and Oran Park became a place of magic.

I slowly worked at it, renovated a little bit, and started building a garden. And it was great in years with marriage. Oran Park was a place of magic. In my book, those chapters in Oran Park were almost written like a kind of poetry. It’s like an ode to a life I knew I was living at a time that was very special.

You have mentioned my divine daughter Adelicia. But my son Pierce was five years old when the marriage failed, and he stepped into very big shoes, that boy of mine. He will soon be 46 and he is still an amazing son to his mother. Rings me every day to be sure I’m well because he lives in Tasmania with his three children. I have two remarkable children. That’s part of the story.

Barbie:

Indeed, as I’ve said in the beginning of our conversation, the strength of family is a very strong theme through your writing. You’ve got that beautiful sort of sun-washed fairy tale vision of the life in Oran Park, but there were also the many years before when you were a struggling single mother and when you went to all sorts of lengths to make sure that the family was honored, including your mother, in making those trips to Western Australia and really keeping the cement of family together. It’s such a strong theme along with the constant theme of health and wellness. You talk a lot about good diet, good nutrition and good physical habits, getting exercise and sunlight, being outdoors and eating well, eating lots of vegetables. You made sure that you cook from home for children and visitors, indeed, who came to the various places where you lived and enjoyed your lunches and dinners.

I’d love to know a little bit more about that because, of course, as you’ve said, you’ve written two books about health and nutrition. It’s obviously something that’s very core to you.

Ashley:

It is. The first two books I wrote were on health, related to families and women, because women hold the health of their families in their hands. And also because of the number of steaming saucepans I had given to friends who I thought could do with a little bit of help with steaming vegetables and putting them on the table every night. It’s very much a core of my life. I was brought up this way. We were ahead of the curve because my grandmother was a clever woman who's picked up on this amazing natural path in the days of white bread and lots of fat in the diet.

I talked about him in my second book – Lawrence Armstrong. He taught our family about going organic and he has played a big role on our health. I was a natural health addict in the womb. So what else could I do, when throughout my life, I had carried this health preset? But I love great, big-roast dinners. I'm not a wowser. I wouldn’t say that you have to be a vegetarian or you have to go to extremes. I don’t believe that.

I believe in balance and I believe in taking time to feed your children well because the hospitals are full of sick children. Children should not have the sugar that they’re given. They’re little people in their small frame and they should be having natural sugars. This is an important ethos of mine, and I could bore you to death with it.

Barbie:

It’s a very important thing – I agree with you. Nutrition, exercise and fresh air, and that focus on family is indeed something dear to my heart as well.

You speak in the book of your children and of your grandchildren, and of the importance of those relationships to you. I really find that such an interesting aspect of you because you have a Renaissance-woman aspect to yourself. You are comfortable sitting in a high-flown board dealing with politicians, with economists who always want the dollar accounted for, with people in positions of power who protect them and guard them. And yet you are equally at home mucking around in a garden, growing roses, welcoming people in to look at Oran Park. Through the story, you seem to fit comfortably wherever you land. The same thing happened when you were a much younger woman in the ’60s with all of your overseas travel to often quite challenging places including Africa, where you had that first really dreadful experience with the birth of your child, also in Asia, and you’ve just dropped into whatever community it is and make connections and friends there. You obviously have a great capacity for connection with people of all sorts.

Ashley:

Thank you! I feel that. I respond to people. I’ve given talks over the years. I’ve trained myself to give lectures and to speak in front of a crowd. I love that ability to feel the warmth coming from the room if you are delivering something that is intriguing to them or they're enjoying. For me, probably, it happens to be about sharing the joy, and it’s the same with the Arts world. If you’re going to put money in the Arts world, into one of my organisations, I want you to come and enjoy this organisation, and that includes politicians. I want you to be a part of the journey and the joy. So I think that comes through with my dealings with fellow human beings.

I'm currently raising money for the Art Gallery of New South Wales in an initiative we have, which will cover five years for indigenous children in remote and regional areas. This is going to be an incredible two-million-dollar project, which friends of mine, lawyers Marco and Jessica, who have been handling the will and talking to them, and they have decided that this money will come to the Art Gallery of New South Wales for these remote and regional children. I feel that as I get older, I’m really into all these remote and regional children – indigenous, European or Australian children. It is very important for me to bring this joy out into these remote areas, and it can be done with good funding and wonderful philanthropic support.

Barbie:

And with the right sorts of conversations had with people on site. Ashley, one of the things – it’s just a minor side that really touched me – you mentioned your connection with the Art Gallery of New South Wales and we’re talking about that just now. One of the exhibitions that you promoted and really championed was the Lady and the Unicorn. It was an exhibition that I attended, having a big Francophile streak within me, and I sat there in absolute, I don’t know, gasping delight. We spent a very long time there. I kept sitting in front of each tapestry and the very good video that was shown as part of the exhibition too, which was very instructive.

I am so glad and grateful that you pushed to have that exhibition there because it’s one of the most beautiful I’ve ever been too. And of course, we can see those things when we’re lucky enough to be in France but it’s not always that we get such wonderful and unusual things in Australia or in Sydney, in fact. So hats off to you and much gratitude for bringing that particular one. It was so exquisite!

Ashley:

Absolutely! And like you, I’m a Francophile. You might have noticed from my book – I have been awarded by the French government a Chevalier des arts et des lettres for the promotion in Australia of French Arts and Culture.

That’s partly due to my involvement in French culture.

I also gave a talk which went online with the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ presiding members, on the love triangle between Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI and Axel von Fersen. That talk went online on Bastille Day and extraordinarily, they have discovered a long-lost letter of Maria Antoinette to Axel von Fersen, which was announced on Bastille Day in Paris. This letter has revealed that she was passionately in love with Axel and that there could have been issues where the little dauphin was Axel's child, and not the King’s.

I’m still deeply involved in French culture, and the Lady and the Unicorn, I knew, was the last chance it would ever be seen away from Paris because it will never leave its home again. It was only leaving because they were renovating the museum and it will never ever be allowed to travel again. Yes, to be transported back to French medieval history is just a joy. With all its references, you have to read through those references that are in the tapestry that tell you the story and many references to the Virgin as the unicorn represents virginal purity.

Barbie:

Yes! Beautiful stuff and, of course, beautiful craftsmanship as well. We are so lucky that we are able to have touched a piece of history like this. Of course, the same thing happens with the National Gallery when we get these marvelous collections and blockbuster exhibitions, as they are referred to, and we always enjoy those a great deal.

Ashley, we could talk for a very long time because you have had a life which is just a little bit longer than mine, not much, and full from the beginning to the end of exciting adventures, trials, tribulations, losses and victories, but also full of love, which is how I see your book. It’s a book of great passion and love for life and for people, for family and for the arts.

Ashley Dawson-Damer, author of A Particular Woman, published by Ventura. It’s a memoir, and I recommend it to all. It’s also partly a history of Australia in many ways because it charts the life that many of us had living through the second half of the 20th century and moving into the 21st.

Thank you so much for spending your time with me today on Living Arts Canberra. It’s been a great honor.

Ashley:

Thank you, Barbie. It’s a great honor for me also.

You can listen to this interview and read the full story on Barbie’s website: www.livingartscanberra.com.au

Living Arts Canberra is a Canberra based, not for profit arts media organisation, established in 2018. LAC founders and principals, Barbie Robinson and Richard Scherer, have lived and worked in Canberra for more than 40 years in media, communications, arts and education fields. We espouse a strong ethic of commitment to the community and have an especial interest in and passion for arts and culture. The LAC website, podcasts and internet radio station offer a voice for artists, arts organisations and community goodwill organisations.